" . . . but it still seemed that some other time,

from some other place,

had invaded the town and was

silently establishing itself" (38).

~ from Badenheim 1939 ~

Out My Window (1930)

by Hanns Kralik (1900 - 1971)

I know the sky looks dark and the city a bit lifeless,

but still the bright yellow trolley and the sense of order

(sometimes a good thing) brought to mind:Yiddish for Travellers

I bought the book optimistically,

thinking to go there one day, to that lost land

where the border guards only know Yiddish . . .

In the capitol of the Yiddish country, there are

shiny green, blue, and yellow trolleys, broad plazas

with delis and patisseries where the small tables

are filled with people reading and arguing and joking

over their strudel and rugelach, sipping tea in glasses.

They place sugar cubes in their mouths; they lovr herring.

They squeeze plump cheeks of nephews ad grandchildren.

The people there are all oddly reminiscent of my relatives,

my aunts and uncles and great - aunts and great uncles,

and all of their relatives who I never met, who never

somehow crossed over, who were isolated perhaps

int this landlocked Yiddish land, where the police

speak Yiddish, where everyone is in terrific health,

vigorous and sometimes portly from all the pastries,

from the lack of stress, from having escaped

everything so thoroughly. [emphasis added]

~ Leonard Orr ~

from his poem "Yiddish for Travellers"

in Why We Have Evening

**********************

Recalling a recent passport renewal, Orr writes:"This process reminded me of my older relatives and their worries. Some of them always carried their passports ("just in case," they said). Some of them had gotten into the habit of having many savings accounts so that cash and documents would be available if needed (the winners in this category, as far as I know, were my ancient aunts Gertie and Rose, who lived in a tiny apartment in Brooklyn and had over one hundred savings accounts spread across all of the boroughs). My parents were baffled by anyone choosing to travel to Europe. When I returned from my first summer in Europe (two months in Paris and London) my father said he it was incredibly brave of me to travel by myself there. He associated Europe with the notion of fleeing."

**********************

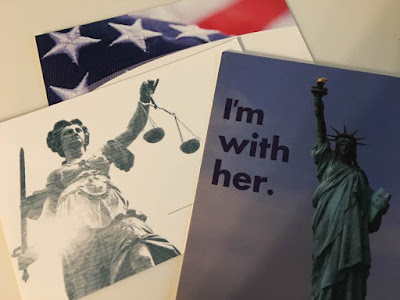

Similar to Kralik's painting is this cover art:

the sky, while not dark, remains high and distant;

the windows, detailed but impassive, retain their secrets.

All of the Badenheim covers are hauntingly quaint,

but I think this artwork by Nancy Lawton is my favorite.

Badenheim 1939 ~ Aharon Appelfeld

It may be true, as a few linguists have observed, that something has been lost in the translation of

Badenheim 1939 from the original Hebrew, but enough has been retained to make it one of the saddest most beautiful books that you might ever care to read. This novel is on my

special list of books that I recommend to everyone.

The lyrical gaiety of the charming resort town is gradually displaced by fear and anxiety. The delicious afternoons of pink ice cream and strawberry tarts are disrupted by the extended "jurisdiction of the Sanitation Department . . . it had been authorized to conduct independent investigations. . . . In the middle of May a modest announcement appeared on the notice board saying that all citizens who were Jews had to register with the Sanitation Department" (11, 20).

Despite this sobering turn of events, the merry - makers strain for a positive outlook:

"The inspectors . . . took measurements, put up fences, and planted flags. Porters unloaded rolls of barabed wire, cement pillars, and all kinds of appliances suggestive of preparations for a pubic celebration.

'There'll be fun and games this year.'

"How do you know?'

'The Festival's probably going to be a big affair this year; otherwise why would the Sanitation Department be going to all this trouble?'

'You're right, I didn't realize.' " (15)

Even as the summer season draws to a melancholy close and the beautiful vacationers are required to board the ominous freight cars, their delusional innocence allows them to voice a false hope, heartbreaking to the reader who knows the horrible reality: " 'If the coaches are so dirty, it must mean that we have not far to go' "(148).

Looking ahead to the "transition" the residents of enchanted Badenheim reassure each other: "'By the way, what language will he sing in?' 'What a question! In Yiddish, of course, in Yiddish!' . . . There was no country as beautiful as Poland, no air as pure as Polish air. 'And Yiddish? . . . There's nothing easier than learning Yiddish. It's a simple, beautiful language, and Polish too is a beautiful language.' . . . The headwaiter was learning Yiddish. Samitzky wrote long lists of words down in his notebook and sat and studied them. . . . in Poland it would be easy to learn. Everyone spoke Yiddish there. . . . 'This is only a transition. Soon we'll arrive in Poland. . . . It's only a transition, only a transition' " (36, 95, 106 - 07, 143).

Their optimism mirrors that of the bookstore patron in Orr's poem above, who "optimistically" picks up a copy of

Yiddish for Travellers, recalling to himself "that lost land," that lost time and place.

Not to trivialize, but reading Badenheim

always brings to mind the song "Desert Moon"

-- yet another lost place.